30

JanuaryPer Stirling Capital Outlook – January

In the 1990s, political strategist James Carville offered one of the most colorful of all economic witticisms when he said: “I used to think that if there was reincarnation, I wanted to come back as the president or the pope or as a .400 baseball hitter. But now I would like to come back as the bond market. You can intimidate everybody.” 1

If anyone doubts the accuracy of that statement, take a moment to research Liz Truss, who has the dubious distinction of being Britain’s shortest-serving Prime Minister (September 6th to October 25th of 2022), before essentially being forced out of office by the response in the British bond markets to her fiscally irresponsible budget and tax proposals.

Truss’ theoretically pro-growth proposals featured both massive tax cuts and the cancelling of planned tax increases and was to be paid for by a big jump in deficit spending, which would require the issuance of more government debt.

In response to her proposals, the value of the pound versus the U.S. dollar plummeted to its lowest level in history, and bond prices fell so sharply that it forced the Bank of England to make emergency purchases of government bonds in an attempt to stabilize the markets. 2 Within a few weeks, Truss had reversed most of her controversial economic policy proposals, but it was too late to salvage her political career.

The concept of markets driving interest rates higher to impose fiscal discipline on government policy is neither new nor limited to Britain. Indeed, economist Ed Yardeni coined the term “Bond Vigilantes” in the 1980s, and we have seen this form of market-imposed discipline in the U.S. during the so-called “Great Bond Massacre” during the Clinton administration and in Europe during the “Eurozone crisis” that started in 2009.3

From our perspective, while the conditions surrounding the recent sell-off in the U.S. (and increasingly global) bond markets are nowhere as extreme as what was experienced in Britain, there are certain similarities that deserve our attention.

Indeed, the similarities between some of the proposals espoused by both Truss and Trump have apparently not escaped President Trump’s attention, as evidenced by his January 23rd ultimatum, during a virtual appearance at the World Economic Forum’s annual meeting in Davos, Switzerland, “that interest rates drop immediately” (a comment clearly targeting Fed Chairman Powell). 4

Particularly in light of President Trump’s very pro-growth agenda, his desire for lower interest rates is entirely understandable. After all, lower interest rates would help to “unlock” the housing market, they would help to improve corporate profitability and would help to strengthen consumer balance sheets.

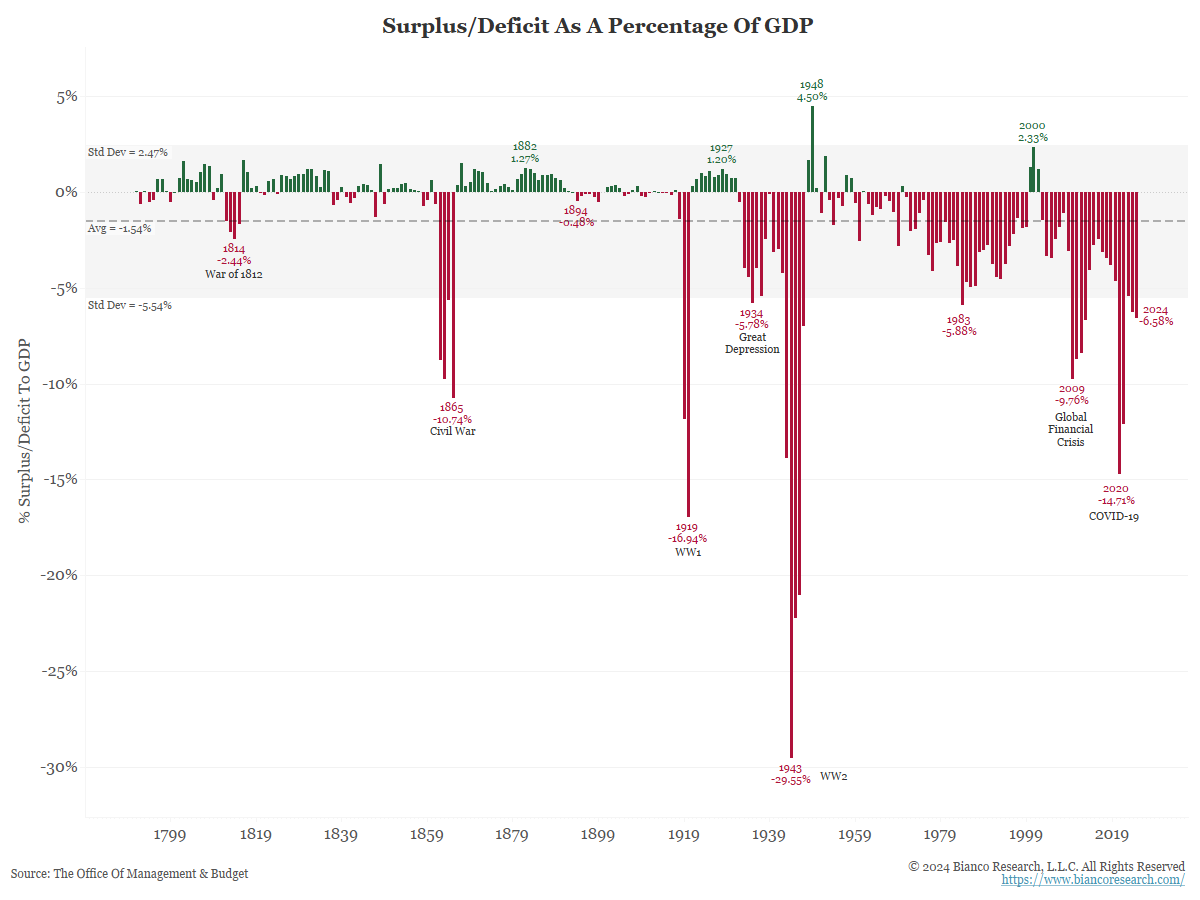

Likely even more important to the President is the impact that lower rates would have on the cost of servicing America’s massive and growing deficit which, relative to the size of the economy, is already at levels previously only seen during major wars or when the government was attempting to stimulate the economy out of significant recessions. This is at a time when the economy is estimated by the Fed to be growing at 2.5% to 3.0%, which is notably above the 2% average growth rate seen over recent decades.

Moreover, it is widely expected that President Trump’s policies will further exacerbate the deficit through tax cuts, potentially higher spending, and higher interest rates. The U.S. is already the world’s biggest borrower, and the U.S. government’s total debt has grown larger than the entire U.S. economy. When the government could borrow at rates below 1%, servicing the debt was manageable. However, at “current borrowing costs, the government’s interest tab is the fastest-growing part of its budget, surpassing defense expenditures in 2024”. 5

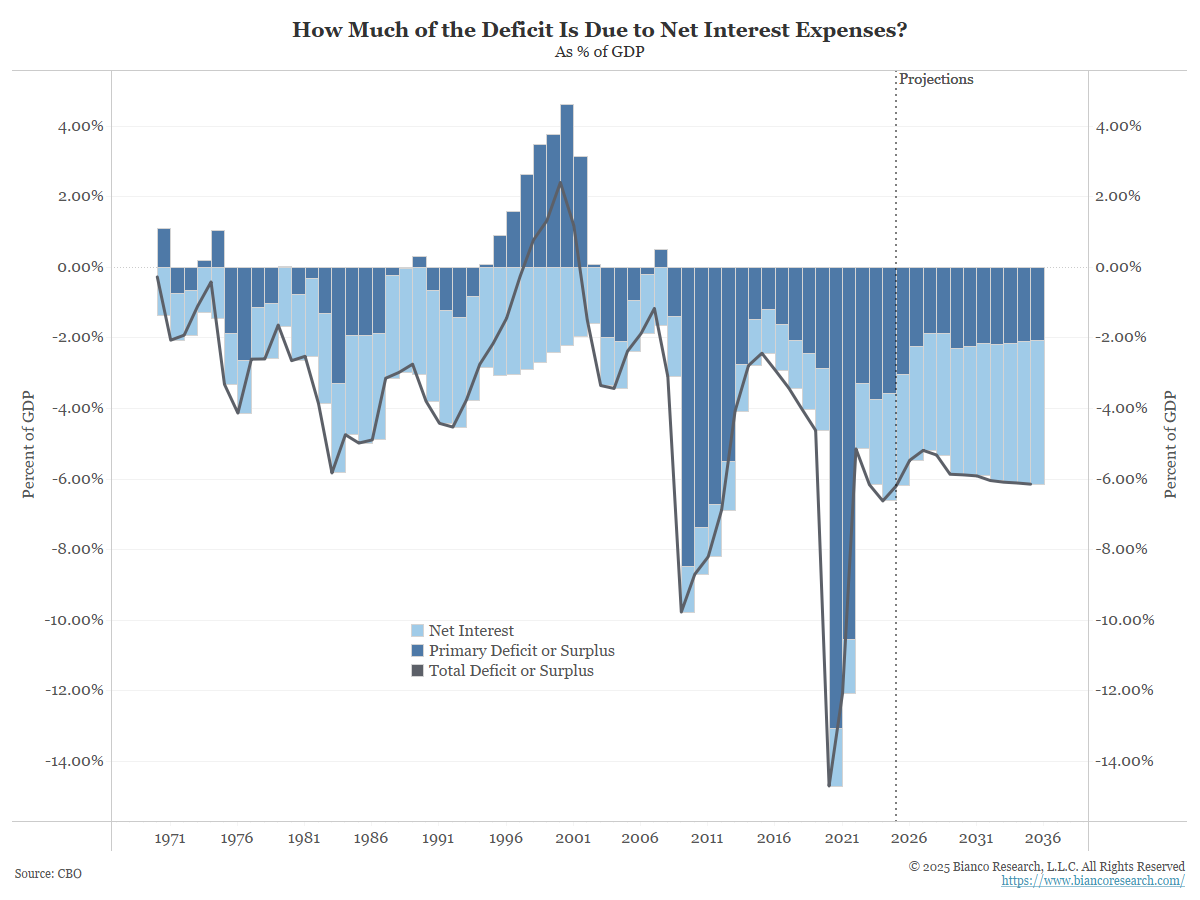

As is illustrated in the above chart from the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office, interest expense now accounts for almost as much (3.10% of GDP) of the annual deficit as does the combination of government spending and principal payments (3.60% of GDP), and over the next decade, interest expense alone is expected to represent more than twice the share of the federal deficit represented by government spending and principal payments on the country’s debt. 6 Importantly, that does not include the anticipated extension of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act legislation that was passed during Trump’s first term in office.

As was recently detailed in a January 15th Wall Street Journal article:

“At the new, higher interest rates, every decision to borrow more money costs even more money. Every 0.1-percentage-point increase in Treasury borrowing costs adds more than $300 billion in interest expenses over a decade. The more the U.S. borrows, the less capital is available for the private sector. And the higher bond yields climb, generally, the more U.S. consumers pay for mortgages, auto loans and credit cards.” 7

However, while President Trump’s “demand that interest rates drop immediately” is understandably desirable, such a demand is also unrealistic and impractical for at least three reasons: The first of those, the critically-important fact that the Fed is independent, and that the President has no legal authority to either issue mandates to Chairman Powell or to replace him before his term expires, should be sufficient on its own right. However, while we question whether Trump would risk the market turmoil that would likely result from an attempt to forcibly remove a Fed Chairman, we believe that it is now a greater risk than we would have imagined as recently as a few weeks ago.

To explain, there is some evidence that President Trump may be using the enhanced immunity provided to a president by the Supreme Court in their 2024 ruling to expand the power of the presidency. The most recent example of this was last week’s firing of the supposedly independent Inspector Generals from over a dozen Federal agencies.

This is contrary a law passed by Congress in 2022 that was specifically designed to keep a president from arbitrarily replacing these independent watchdogs, and which specifically requires the White House to provide substantive rationale for terminating any Inspector General and requiring a 30-day notice to Congress before any such termination can take place. 8

If President Trump is indeed attempting to expand the power of the presidency, then an attempt to take away the Fed’s independence is arguably no longer out of the question. However, even in the most regrettable event of the President compromising the Fed’s independence, it would not change the fact that the Fed has very little ability to control intermediate and longer-term rates.

In fact, the Fed only sets two rates. One, the rather infrequently used Discount Rate, is the rate charged for very short-term loans (24 hours or less) made to a bank by the Federal Reserve. 9 The second rate set by the Fed (the one that the President is lobbying to have lowered) is the Federal Funds Rate (Fed Funds), which is the “the interest rate at which depository institutions (banks and credit unions) lend reserve balances to other depository institutions overnight on an uncollateralized basis”. 10 It applies to loans made only on an overnight basis.

In other words, the Fed only controls ultra-short-term rates, and virtually all longer-term rates are set by the markets, which both brings us back to the theme of this report and provides a nice segue to the third reason why jawboning the Federal Reserve is, in our opinion, very unlikely to produce lower intermediate and longer-term interest rates.

Quite simply, the bond market is even more powerful than the President, and it is the market, not the president or even the Fed, that will set most interest rates. Indeed, jawboning the Fed could even make it more difficult for the Fed to lower rates as, if the Fed cuts rates and it is perceived by investors that they bowed to political pressure, it would weaken the inflation fighting credibility of the Fed and potentially push everything but ultra-short rates even higher.

In bond markets, interest rates and prices move in the inverse of one another, so the markets effectively set interest rates when investors survey factors like inflation, economic strength, deficit levels, monetary policy, government spending, etc., and decide what they are willing to pay for a bond of a given rate, maturity and credit quality.

In an environment like the present, where investors are concerned that inflation is still not under control, the lowering of interest rates by the Fed is akin to squeezing one end of a balloon. While one side becomes smaller, the other end of the balloon becomes larger. Similarly, by lowering ultra-short-term rates (one side of the balloon) and thus potentially increasing the risk of higher inflation, the Fed is actually pushing intermediate and longer-term interest rates higher (i.e., making the other end of the balloon larger).

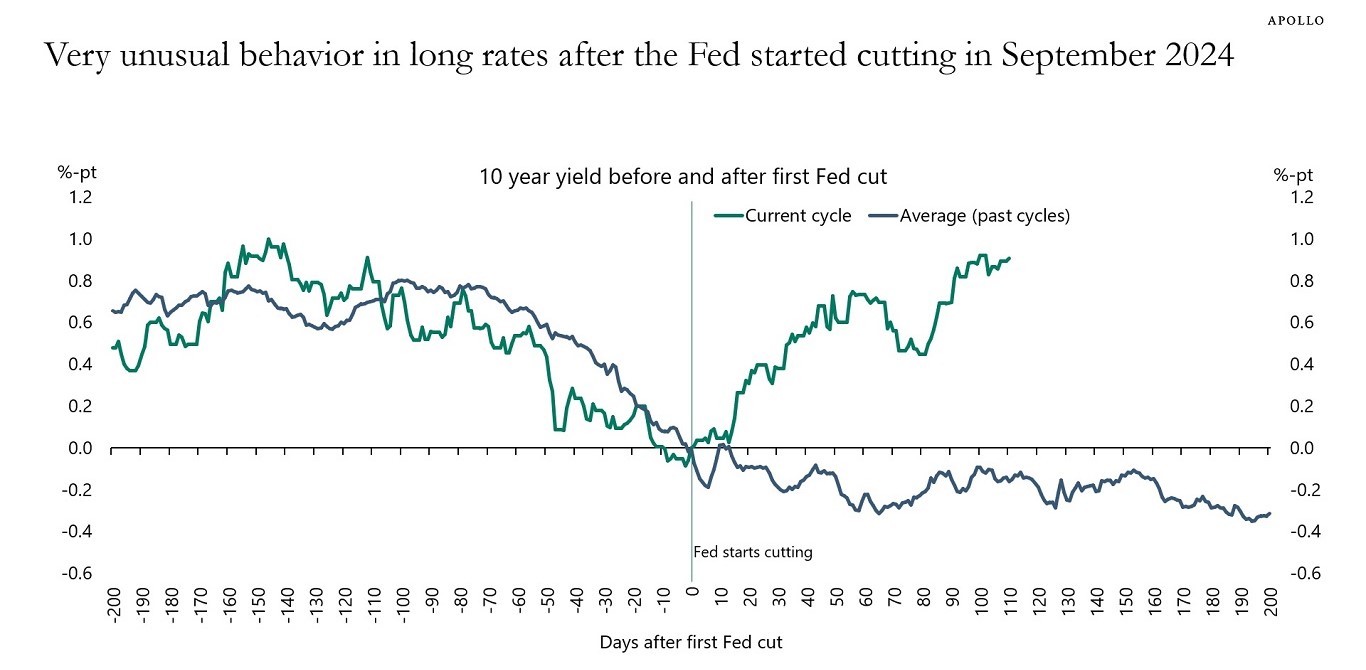

You can see this phenomenon very clearly in the following chart. Unlike times when rates are being lowered in response to economic weakness or sharp declines in inflation rates, in which case longer-term, market-set rates will generally follow ultra-short rates lower (the dark grey line in the following chart), the opposite (green line) is happening this time.

This cycle, the Fed cut ultra-short-term rates by one full percent, and markets reacted by pushing long-term interest rates higher by almost the same amount. From our perspective, the message of the markets is that the Fed still has more work to do in battling inflation, that they should not have cut rates, and should not cut rates any further, until that battle is won.

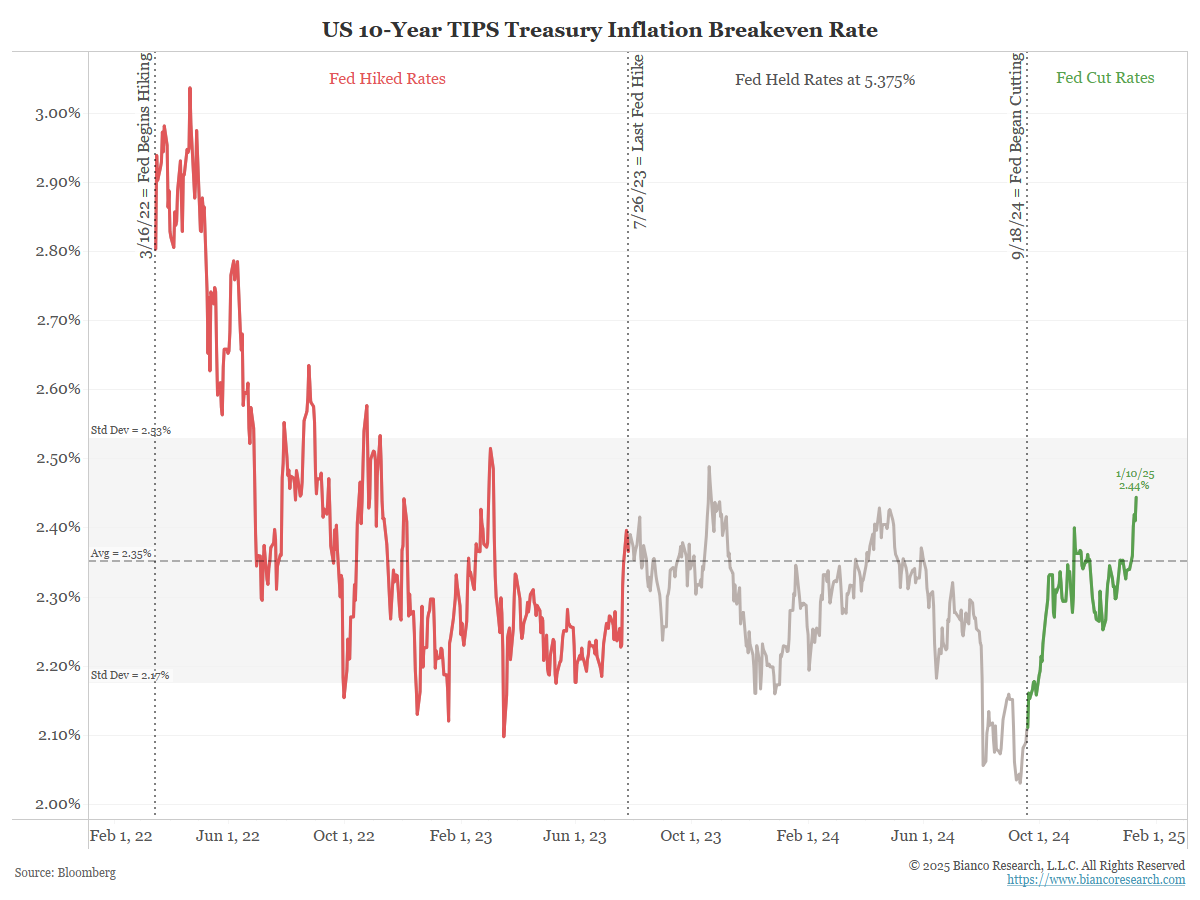

As evidence to support our opinion, we would point to the following chart of the 10-year Treasury “breakeven rate”, which is basically a bond market-based estimate of inflation expectations for the next ten years. You will note that inflation expectations fell when the Fed was raising rates (red line), stayed relatively flat while Fed policy was on hold (grey line), and have moved notably higher ever since the Fed started lowering rates.

In other words, markets seem to be suggesting that the Fed is risking higher inflation and even higher longer-term interest rates by deciding to cut short-term rates when inflation was still undesirably high. Remember that inflation and interest rates move in unison, and in the opposite direction of bond prices.

Importantly, Scott Bessent, who is Trump’s nominee for Treasury Secretary, wants to reverse the Biden administration’s emphasis on the issuance of shorter-term Treasury bills and shift back toward longer-term issuance, which will also tend to drive yields higher. 11

The bottom line is that, with the economy already growing at a rapid pace, with inflation still well above the Fed’s 2% target, and there being a variety of potential outcomes related to tariffs, mass deportations and tax cuts that could further exacerbate inflation, a conflict between the White House and the Fed seems increasingly likely. At the same time, President Trump is likely to be very frustrated by his inability to force the bond market to do his bidding.

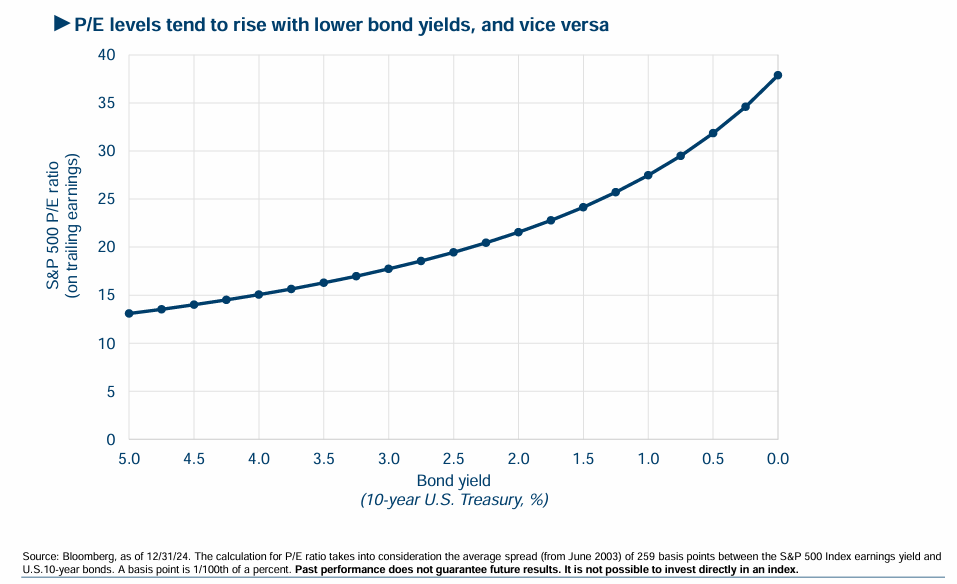

If we are correct, it could be a source of increasing uncertainty for the markets that could at least dampen stock and bond returns and may ramp up risk and volatility in both asset classes. While the reasons for such an impact in the bond markets are fairly self-evident, the impact on the equity markets could be at least as significant for a number of reasons, including the fact that stock and bond prices have spent the last year closely correlated with one another and the fact that higher interest rates have historically tended to cause a phenomenon called multiples compression, where investors tend to assign less value to each dollar of company earnings, thus limiting the upside potential of an equity market.

Yes, after a two-year period when almost nothing could go wrong for the stock market and a three-year period when almost nothing could go right for the bond market, there is a whole new level of uncertainty coming out of Washington, and that could ramp up volatility even further.

However, despite this fact, we believe that it is too early to get bearish on equities and probably far too late to get bearish on the bond markets.

While the stock market is very expensive relative to corporate earnings, there are elements of the Trump agenda that should be very equity market friendly. These include a proposed reduction in corporate taxes from 21% to 15%, a pledge to dramatically reduce regulatory requirements, and what increasingly appears to be an intent on the part of President Trump to run the country as if it were a public company, complete with cost cutting measures and the making of significant capital investment.

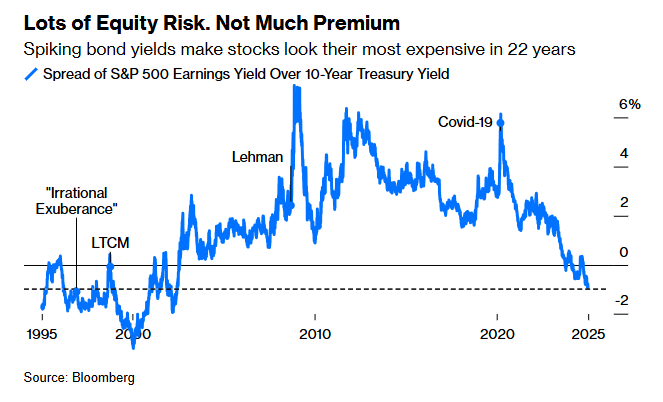

In contrast, high-quality, long-term bonds (as represented by long-term Treasury notes and bonds) have just suffered their worst losses in ninety years. 12 The good news is that, while bonds may still be in a bear market, they are the least expensive relative to equity prices in 22 years. This comparison is based upon a ratio of the S&P 500 earnings yield (the inverse of the price-to-earnings ratio) to the dividend yield on Treasuries.

In addition, with bonds now offering relatively attractive yields, there is an offset that may help to keep fixed income total returns positive even in the event that rates move higher.

In light of this environment, some of Wall Street’s most respected analysts have stated their opinion that bonds may actually outperform equities in 2025, while others are hypothesizing that a traditional portfolio mix of 60% equities and 40% bonds could produce attractive risk-adjusted returns for the first time in years.

We believe that it still makes sense to stay invested, but that the uncertainty of the current environment may make diversification across asset classes increasingly prudent over the foreseeable future.

Disclosures

Advisory services offered through Per Stirling Capital Management, LLC. Securities offered through B. B. Graham & Co., Inc., member FINRA/SIPC. Per Stirling Capital Management, LLC, DBA Per Stirling Private Wealth and B. B. Graham & Co., Inc., are separate and otherwise unrelated companies.

This material represents an assessment of the market and economic environment at a specific point in time and is not intended to be a forecast of future events, or a guarantee of future results. Forward-looking statements are subject to certain risks and uncertainties. Actual results, performance, or achievements may differ materially from those expressed or implied. Information is based on data gathered from what we believe are reliable sources. It is not guaranteed as to accuracy, does not purport to be complete and is not intended to be used as a primary basis for investment decisions. It should also not be construed as advice meeting the particular investment needs of any investor.

Nothing contained herein is to be considered a solicitation, research material, an investment recommendation or advice of any kind. The information contained herein may contain information that is subject to change without notice. Any investments or strategies referenced herein do not take into account the investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of any specific person. Product suitability must be independently determined for each individual investor.

This document may contain forward-looking statements based on Per Stirling Capital Management, LLC’s (hereafter PSCM) expectations and projections about the methods by which it expects to invest. Those statements are sometimes indicated by words such as “expects,” “believes,” “will” and similar expressions. In addition, any statements that refer to expectations, projections or characterizations of future events or circumstances, including any underlying assumptions, are forward-looking statements. Such statements are not guarantying future performance and are subject to certain risks, uncertainties and assumptions that are difficult to predict. Therefore, actual returns could differ materially and adversely from those expressed or implied in any forward-looking statements as a result of various factors. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of PSCM’s Investment Advisor Representatives.

The information presented is not intended to be making value judgements on the preferred outcome of any government decision or political election.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. The investment return and principal value of an investment will fluctuate so that an investor’s shares, when redeemed, may be worth more or less than their original cost. Current performance may be lower or higher than the performance quoted.

Definitions

The Standard & Poor’s 500 (S&P 500) is a market-capitalization-weighted index of the 500 largest publicly-traded companies in the U.S with each stock’s weight in the index proportionate to its market. It is not an exact list of the top 500 U.S. companies by market capitalization because there are other criteria to be included in the index.

The Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) is a price-weighted average of 30 actively traded “blue chip” stocks, primarily industrials, but includes financials and other service-oriented companies. The components, which change from time to time, represent between 15% and 20% of the market value of NYSE stocks.

The Gross Domestic Product Price Index (GDP) measures changes in the prices of goods and services produced in the United States, including those exported to other countries. Prices of imports are excluded.

Indices are unmanaged and investors cannot invest directly in an index. Unless otherwise noted, performance of indices does not account for any fees, commissions or other expenses that would be incurred. Returns do not include reinvested dividends.

Citations

-

“The Daily Prophet: Carville Was Right About the Bond Market”, Robert Burgess, Posted 1/29/2018, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-01-29/the-daily-prophet-carville-was-right-about-the-bond-market-jd0q9r1w?sref=YfRIauRL

-

“Liz Truss”, Wikipedia, As of 1/27/2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liz_Truss

-

“Bond vigilante”, Wikipedia, As of 1/27/2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bond_vigilante

-

“High Interest Rates Are Hammering Investors. What Lies Ahead Could Be Worse.”, Randall W. Forsyth, Posted 1/24/2025, https://www.barrons.com/articles/high-interest-rates-deficit-bonds-borrowing-trump-policies-23a39f5b?mod=djem_b_This

-

“High Interest Rates Are Hammering Investors. What Lies Ahead Could Be Worse.”, Randall W. Forsyth, Posted 1/24/2025, https://www.barrons.com/articles/high-interest-rates-deficit-bonds-borrowing-trump-policies-23a39f5b?mod=djem_b_This

-

“Some Perspective on U.S. Interest Costs”, Breg Blaha, Posted on 1/24/2025, https://www.biancoresearch.com/visitor-home/

-

“Bond Market Sends Warning to Trump and Republicans on Tax Plans, Richard Rubin, Sam Goldfarb, Posted on 1/15/2025, https://www.msn.com/en-us/money/markets/bond-market-sends-warning-to-trump-and-republicans-on-tax-plans/ar-AA1xgIXy?ocid=hpmsn&pc=AV01&

-

“Trump fires inspectors general from more than a dozen federal agencies”, Manu Raju, Alayna Treene, Morgan Rimmer and Annie Grayer, Posted on 1/25/2025, https://www.cnn.com/2025/01/25/politics/trump-fires-inspectors-general/index.html

-

“Discount Rate Defined: How It’s Used by the Fed and in Cash-Flow Analysis”, Adam Hayes, Posted 6/30/2024, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/d/discountrate.asp

-

“Federal funds rate”, Wikipedia, As of 1/27/2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Federal_funds_rate

-

“Bond-Yield Breakout Is Much More Than Inflation”, John Authers, Posted 1/7/2025, https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2025-01-08/bond-yield-breakout-is-much-more-than-inflation?sref=YfRIauRL

-

“Bonds Had Their Worst Decade in 90 Years. Why Now Could Be the Time to Buy.”, Ian Salisbury, Posted 1/22/2025, https://www.barrons.com/articles/bonds-interest-rates-816c9446?siteid=yhoof2